There are many buildings I have gained great affection for over the years only to see them demolished. But Hounslow Civic Centre holds the record for the shortest time between first swoon and the wrecking ball – I was privileged to go on a tour of the building in March 2019, one month before the Council moves out and the developers take over to turn the site into housing. In this post, I want to pay tribute to the “full circle” of the building’s life, before it is gone for good.

I’m not sure it is for me to judge its merits on purely architectural grounds. But I do feel that Hounslow Civic Centre represents something important in the history of London’s local government. It was one of only a handful of London municipal HQs built in the 1970s, (Kensington & Chelsea, Hillingdon, Harrow and Sutton also spring to mind): the last great projects before the money ran out in the economic crisis of the mid-Seventies. They perhaps mark the end of a progressive phase of London government modernisation and expansion before cuts and retrenchment set in.

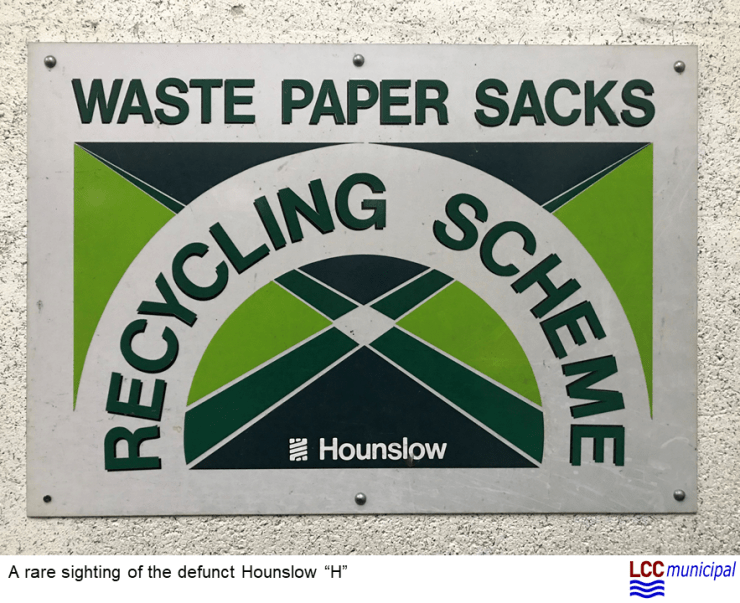

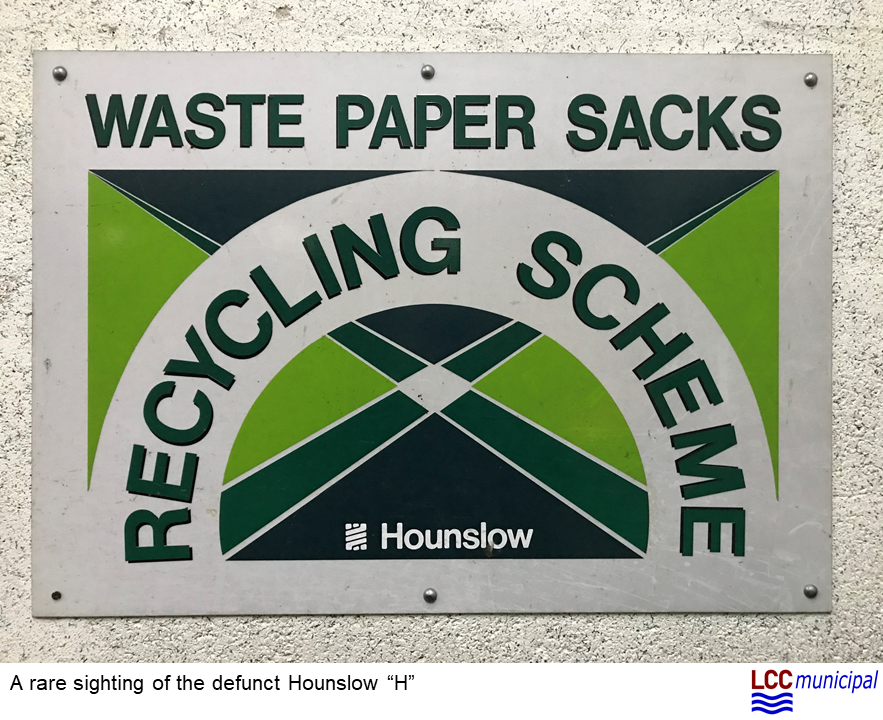

There are plenty of things to love about Hounslow’s municipal complex: it was designed by the Borough’s in-house architects’ department (remember them?); it was built in the form of an “H” in what might have been an early bit of municipal branding; it helped to give the Borough a much needed sense of identity and common cause among its citizens who were scattered from Chiswick to Feltham; and it is full of bold Seventies design features that only those without a soul could fail to be charmed by.

So, let us celebrate Hounslow Civic Centre. But before we do, some words on how this London Borough came about…

The birth of the London Borough of Hounslow

When Herbert’s Royal Commission on Local Government in Greater London reported in 1960, it did not propose anything that looked like the modern London Borough of Hounslow.

Under the Commission’s plans for 52 London Boroughs, Feltham Urban District Council was to be replaced with a new Borough along with Staines and Sunbury (combined population: 129,000), while the boundaries of the Borough of Heston & Isleworth would have remained unchanged (population: 105,000). Finally, a third new authority would replace the Boroughs of Brentford & Chiswick and Acton (combined population: 122,000).

The Government’s White Paper of November 1961 presented a proposal for fewer, larger Boroughs. In this revised scheme Borough number 27 would comprise the area covered by the Boroughs of Heston & Isleworth and Brentford & Chiswick and the Urban District Councils of Feltham, Sunbury and Staines. It would be a large authority (combined population of 291,000) with a long funnel shape, having the A4 and A30 roads as its spine.

The next stage in this drawn out process was a series of conferences to determine the final size and shape of Greater London and its Boroughs. Harry Plowman, the Town Clerk of the City of Oxford, presided over the discussion of Borough 27 and its neighbours at a meeting held in Ealing Town Hall on 4th June 1962. By now the Minister had decided to exclude the Sunbury and Staines Councils from Greater London (such that they would move from Middlesex to Surrey), to leave a revised proposal which accorded with the present-day London Borough of Hounslow.

The June 1962 conference allowed the existing authorities to air their views and disagreements. The majority group on Brentford & Chiswick Council preferred a proposal by the Borough of Ealing which would have seen them grouped with Ealing and Acton. Under this plan, Heston & Isleworth and Feltham would have been grouped with the Borough of Southall. Brentford & Chiswick felt that Borough 27 would have “little cohesion” and that they “had no associations at all with Feltham and few with Heston & Isleworth”. On the other hand, the minority group on the Council, while also rejecting Borough 27, favoured a link up with the Boroughs of Hammersmith and Fulham instead.

Feltham Urban District Council still favoured exclusion from Greater London altogether and they found the idea of Borough 27 “quite ridiculous”. If they were to be included in Greater London, then they proposed an alternative grouping of Feltham, the Cranford wards of Heston & Isleworth and the Urban District Councils of Yiewsley & West Drayton and Hayes & Harlington to form a new “London Airport Authority”.

Only the Borough of Heston & Isleworth supported the White Paper’s proposal. Their justification was that the primary communication links in their existing area ran from east to west rather than north to south, such that a grouping with its Feltham and Brentford & Chiswick neighbours was preferable to one that included Southall.

Yet the protests came to nothing and Borough 27 (of 34) survived as Borough 25 (of 32) in the final approved scheme.

“Borough 25” would not, of course, last as a name. The local Joint Committee of the three predecessor authorities put forward “Osterley” as a proposal, a title which the Ministry of Housing and Local Government concluded had “no charm”. “Brentford” was also considered, given its historical associations, but – so as to avoid confusion – this idea was killed off when the Wembley/Willesden grouping alighted on the name “Brent”.

Thus, the London Borough of Hounslow came in to being in 1965 – a coalition of the largely unwilling. None of three predecessor authorities possessed a Town Hall of a size capable of housing all the functions of a new London Borough and a decision was taken quickly to build a new Civic Centre. Yet while the decision was swift, it would be ten years before the building opened.

Hounslow Civic Centre is born

“Civic centres are conceived and born. Hounslow’s was conceived a decade ago at a time when local government was filled with excitement at the future which lay ahead. The community was affluent, aspirations were high and London’s government had been reorganised to meet the growth in services which everyone desired” Hounslow Borough News, October 1975

So proclaimed the Council’s newsletter, capturing perfectly the spirit of confidence and adventure of ten years earlier. But by 1975 much had changed, and the article was forced to concede that:

“The Civic Centre is born into a national economic crisis with inflation causing painful but unavoidable rate increases. A watchful community now demands a cut-back in the rate of growth in local government expenditure and even as the Civic Centre went through the final stages of its birth, Councillors were forced to strip it of non-essential items once thought fit for this new born babe.”

Still, at least it was completed. Sutton’s Civic Centre, which opened around the same time, remained a work-in-progress, its final phase (including the Council Chamber) abandoned forever as the UK’s financial outlooked worsened.

Even before the London Borough of Hounslow had come into existence, Heston & Isleworth had earmarked a site in Lampton Park, just north of Hounslow Central underground station, for a new Town Hall complex. The plot of land had cost them just £20,000 and would prove to be a shrewd investment.

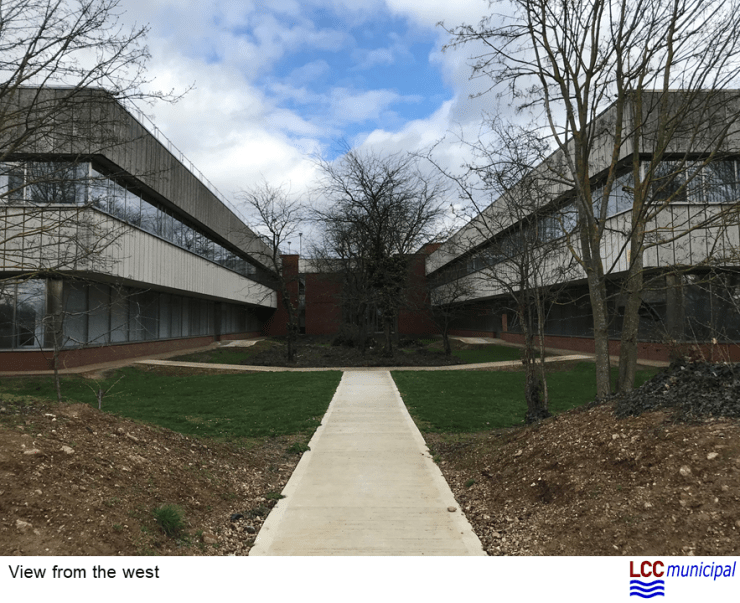

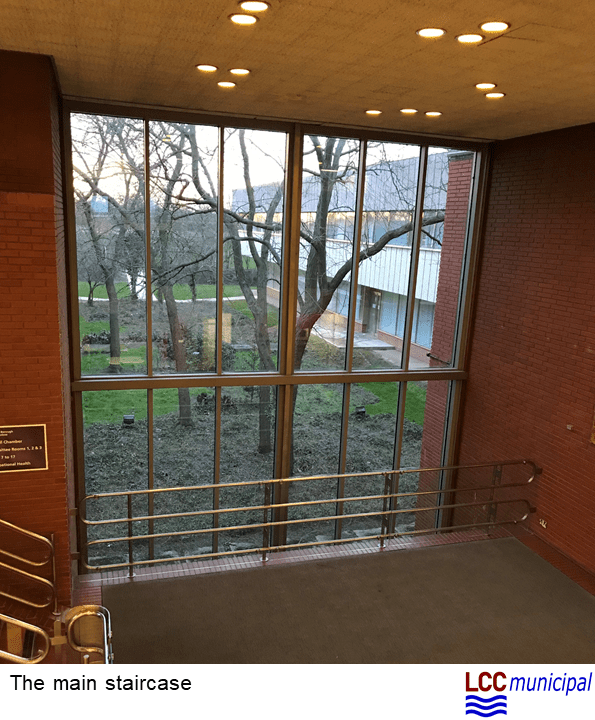

It fell to the Borough Architect, George Trevett and his Deputy, Brian Noble, to design the building. Flexibility was a key consideration as it was anticipated that policy, legislation and the changing economic climate would all contribute to regular reorganisations as services expanded and contracted. Their two-storey design resulted in four “pavilions” joined together by a central spine containing the main staircase. Three of the pavilions housed sizable open plan offices over each floor, adopting the principles of Eberhard and Wolfgang Schnelle’s fashionable Bürolandschaft (“office landscape”) concept in support of the desired goal of a flexible layout.

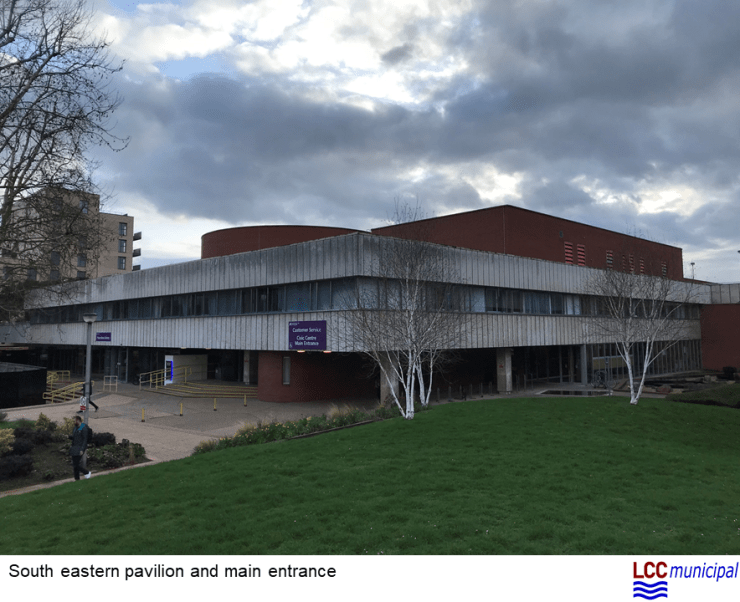

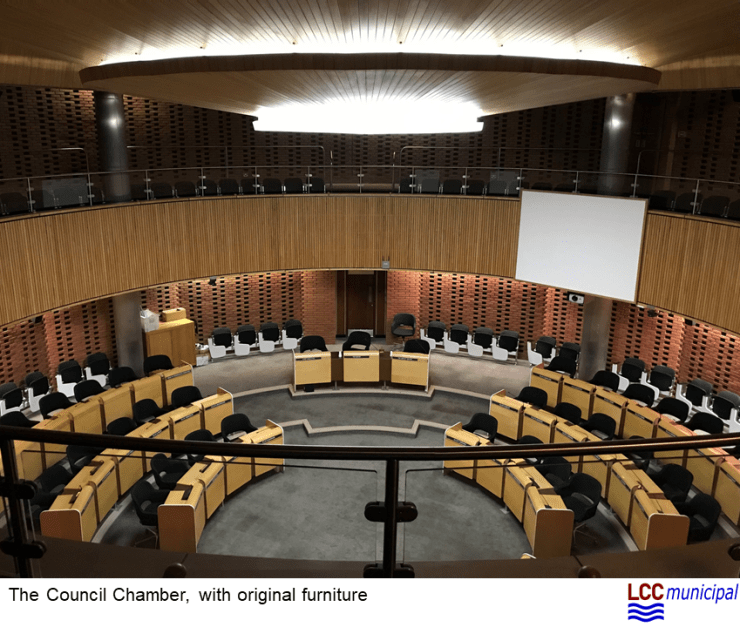

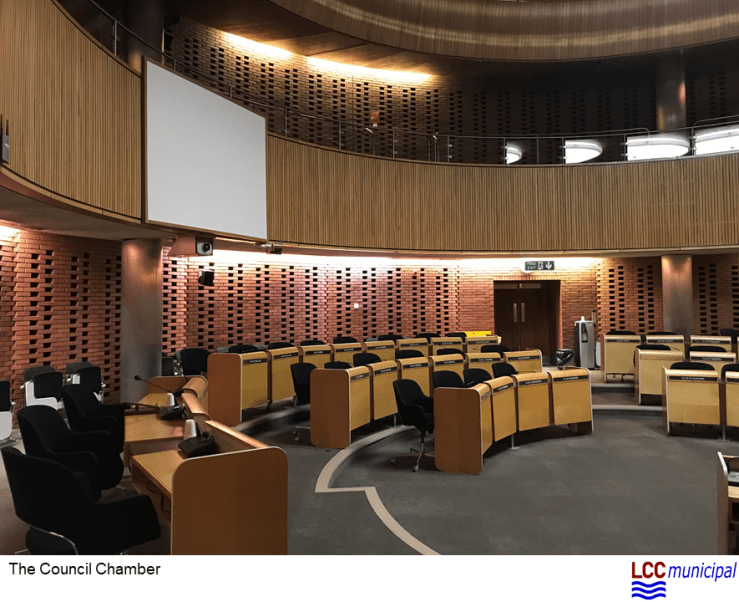

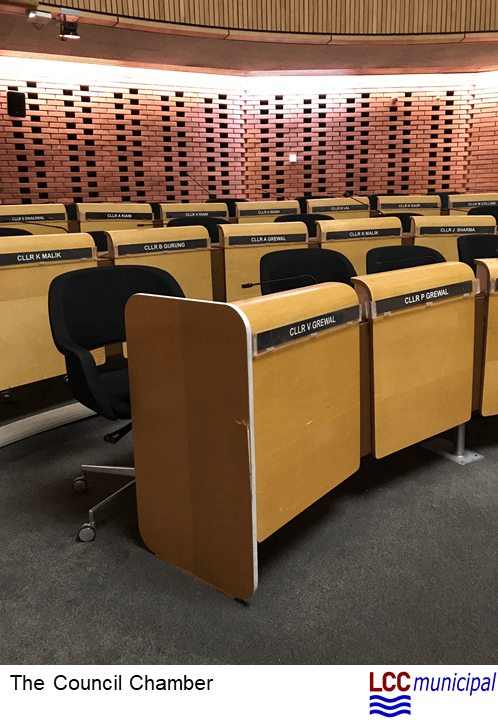

The fourth pavilion, on the south east corner of the site, was home to the public reception areas and a formal civic suite, including a distinctive circular (well, twelve-sided in fact) Council Chamber.

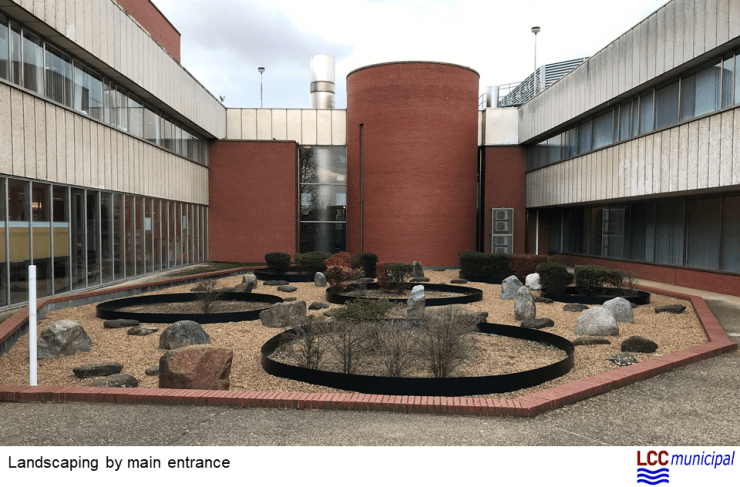

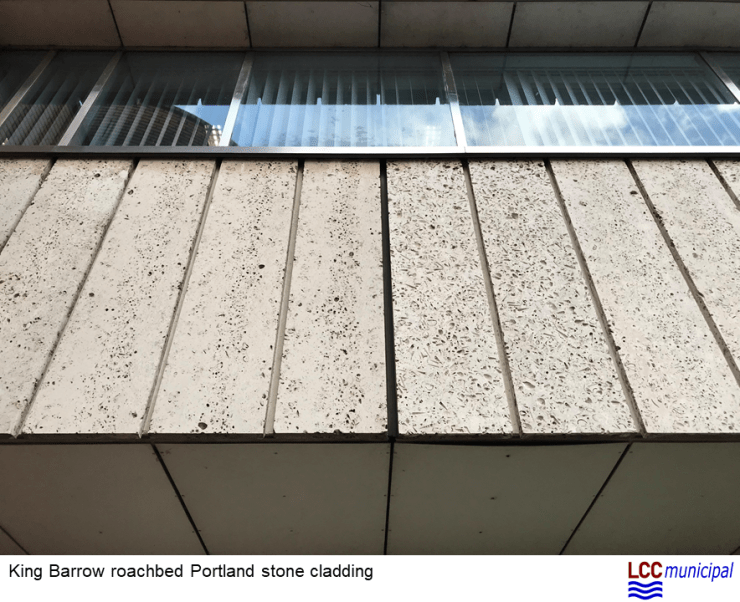

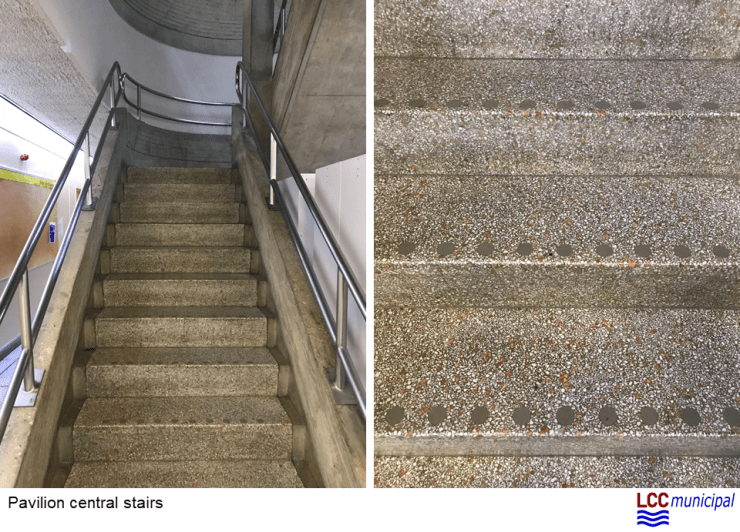

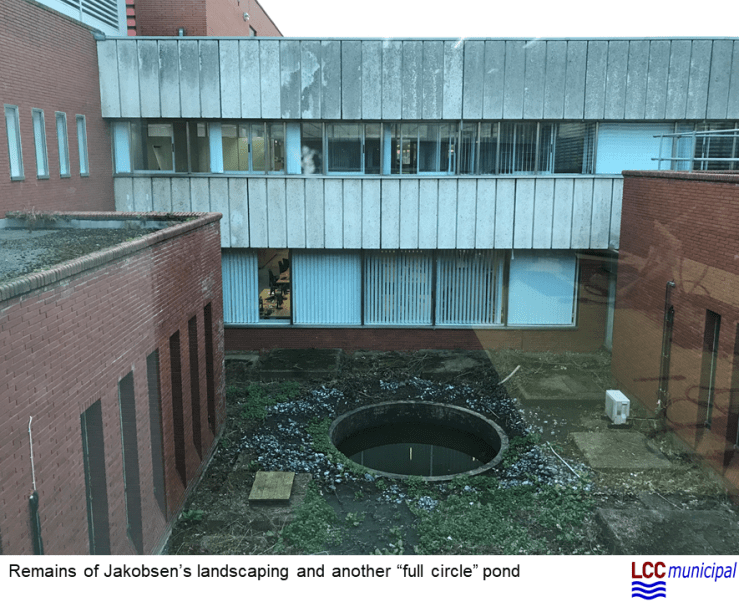

Construction began in 1972 with MJ Gleeson appointed as the main contractors and Preben Jakobsen as the landscape architect. The reinforced concrete structure used waffle slab roofing and floors and was attractively clad in Portland stone and specially designed long, thin red engineering brick. Particular consideration had to be given to the site’s location directly beneath the latter stages of the Heathrow flight path descent with good sound insulation throughout.

On 17 November 1975, at a cost of £4.9 million for the build and a further £1 million for the fit out, the building was ready to welcome its first occupants. Of the end result, Pevsner was moved to write:

“The straightforward modern style, achieved here with an elegance lacking in some of Hounslow’s cheaper developments, is characteristic of the work of the first decade of the borough’s architect’s department.”

For the first time, all of the Borough’s principal services could be co-located. Since 1965, officers had been spread across Hounslow: the Director of Housing had been based in Feltham, while the Director of Social Services could be found in Brentford. Finally, Heston & Isleworth’s Treaty Road Town Hall was able to be vacated along with the leased Hounslow House.

Fast forward to March 2019

On the middle of a Wednesday afternoon in March, I found myself standing outside the Civic Centre for my first, and almost certainly last, visit. Thanks to the generosity of Thomas Ribbits, Hounslow’s Head of Democratic Services, a comprehensive and immensely enjoyable tour beckoned.

I have to confess that the first thought that entered my head was that I couldn’t believe that this was a building about to be razed to the ground. It has aged well externally. Without even seeing the alleged German interior design principles at work (it turns out they are long gone), I was struck by how modern and European it felt. I’ll make the obvious point to get it out of my system: this progressive building had opened in the year of the first European referendum when a positive vision for the UK’s role in Europe was being developed, and here I was in March 2019, with the end in sight for both the Civic Centre and the British European project.

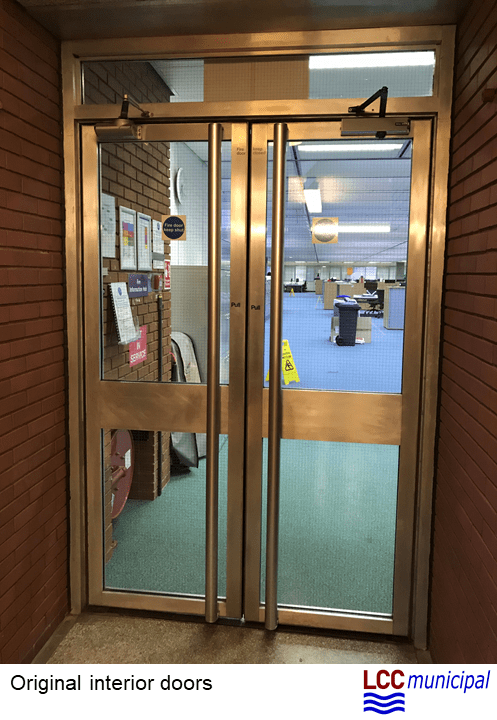

If a slight sadness had set in at that thought, it wasn’t immediately lifted on arriving in the main public entrance and reception area. This heavily-used space must have seen a number of renovations and refurbishments and, having been shorn of original features, had a somewhat bland twenty-first century corporate feel to it – the visual language of modern customer service rather than old-school public service. It was to be the last time I was disappointed, as what followed will stay with me for a long time (not least because I managed to take 200 photos…).

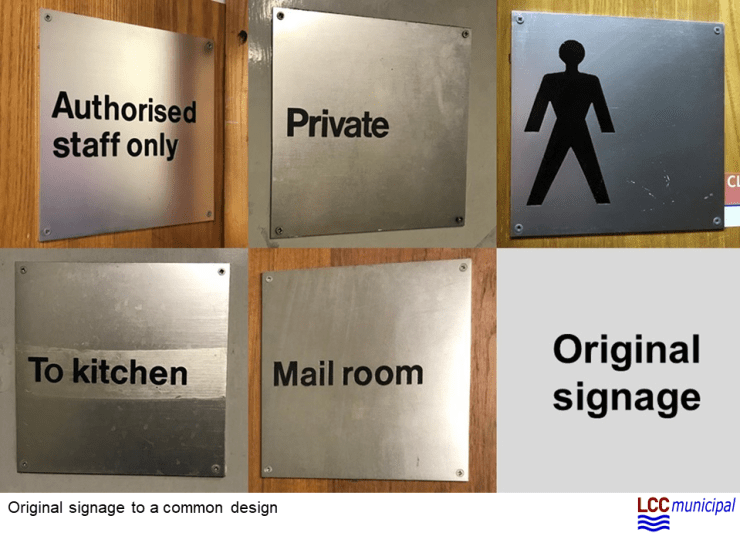

A walk up the main staircase is a journey from white painted plasterboard to concrete waffle-slab ceilings – from 2019 straight back to 1975 in a disorienting transition. We spent the next three and half hours covering every aspect of the building and what a thrill it was. Satisfyingly, the rest of the physical fabric of the interior had not significantly changed from the 1970s and much entertainment was had seeking out aspects of the original designs, features and materials which had given the space its unique character.

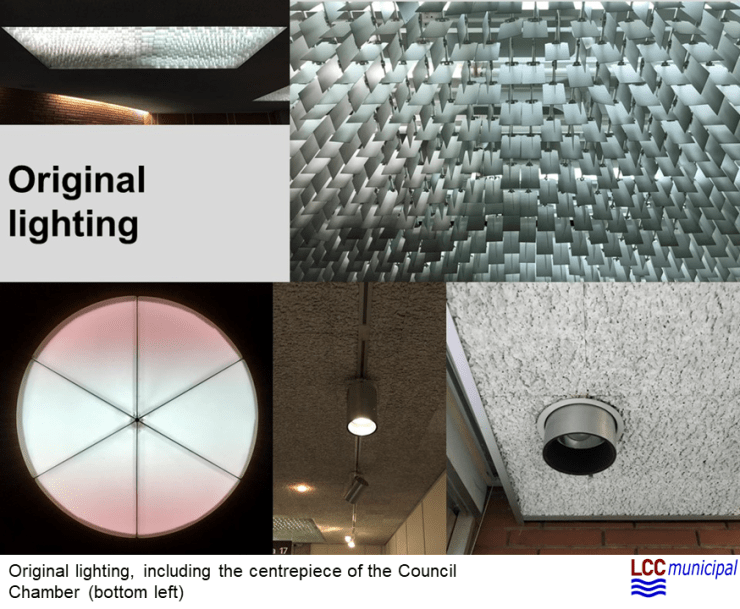

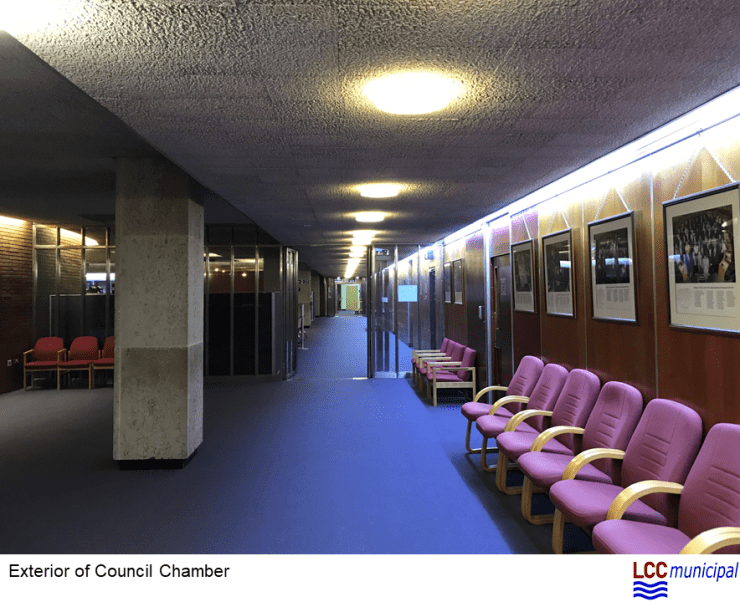

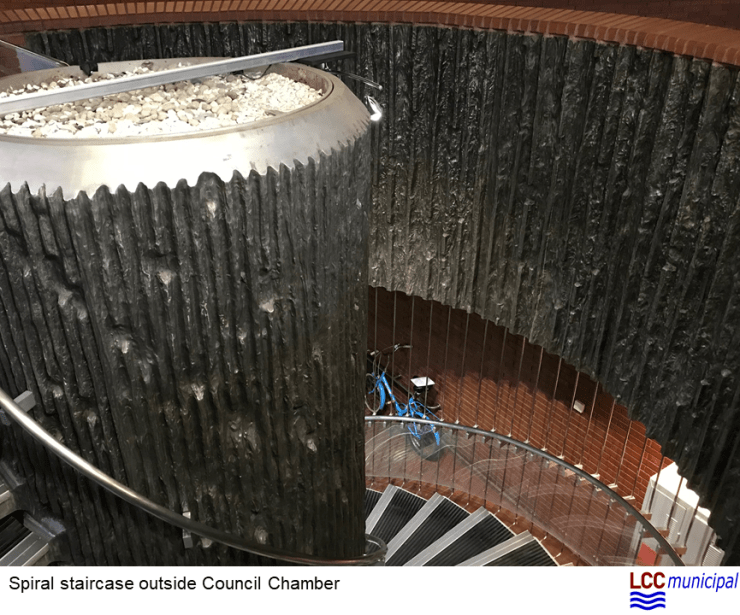

Highlights were many and varied. Having passed through some extraordinary metal doors, which had the rough texture of a Bill Mitchell concrete creation, we arrived in the public space around the Council Chamber to find some truly magnificent light fittings in an aesthetic that might be described as “Seventies Arndale Centre”. And then there was the full circle (you get my theme…) of the Council Chamber itself, an intimate space which – cliché alert – provided a genuine “wow” factor. It felt completely contemporary and one could be forgiven for thinking it was about to host its first Council meeting – in fact it had held its final scheduled session the night before.

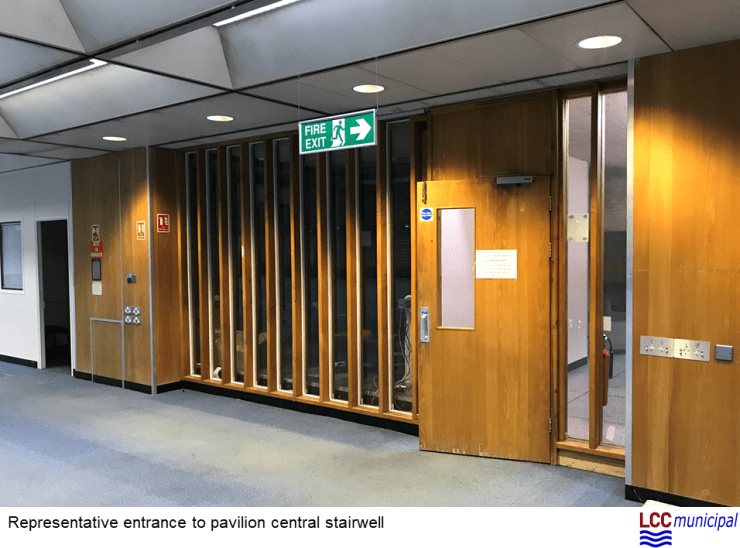

The ceilings of the remaining three open plan office pavilions also impressed: a large grid of strip lights, each one placed in an inverted prism housing. The central stairwells of each pavilion were a mini-brutalist delight, complete with communal staff locker space conveniently placed around the stairs.

Some things haven’t necessarily lasted. The generous expanses of the open plan floors remain, but the strict principles and nuances of Bürolandschaft have not survived, such that the linear desk layout would be familiar to anyone who has worked in an open plan office of the past twenty years. Also, Jakobsen’s external landscape design has largely disappeared over the years, but their concrete paving slabs of various sizes and heights (surely a Health & Safety inspector’s nightmare) have survived in places.

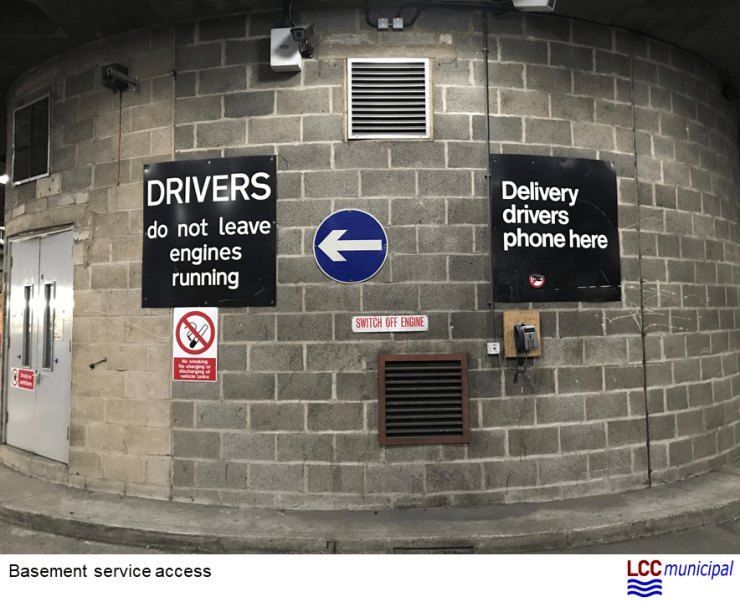

Anyway, I will let the pictures do the talking, and I hope you enjoy the images at the bottom of the page.

You won’t be surprised to hear that I will be saddened to see Hounslow Civic Centre go. But I offer up this overview of the building not to generate a sense of misty-eyed nostalgia, but rather to celebrate an important contribution to London’s municipal life. As we passed through the spaces, it was difficult not to reflect on the micro-social histories that had played out in them: the working relationships forged, the meetings held, the decisions taken and the citizens helped. So I pay tribute to all those who have worked there and wish the current staff the best of luck as they move to their new home.

I would like to express my sincere thanks to Thomas Ribbits for being so generous with his time and to the staff of Hounslow Civic Centre for such a warm welcome. I haven’t had this much fun on a Wednesday afternoon (in fact, evening by the time I left) for years.

Sources

Hounslow Borough News, LB Hounslow (October 1975) Special Civic Centre Edition

Building Dossier: Civic Centre, Hounslow, England. Building 25 February 1977

Royal Commission on Local Government in Greater London 1957-60 HMSO (1960)

London Government: The London Boroughs. Report Presented to the Minister of Housing and Local Government by S. Lloyd Jones et al HMSO (1962)

London’s Town Halls RIBA/English Heritage (1999), Gazetteer of London Town Halls by Jonathan Clarke, Peter Guillery and Joanna Smith

The Buildings of England London 3: North West, Penguin (1999) by Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner, edition

Postscript

Always on the lookout for examples of old branding, I was pleased to find just one instance of the old Hounslow “H” (fun fact: this logo was introduced in 1975 to coincide with the opening of the Civic Centre)…

GALLERY